An image has been going around, showing how to spend a million credits in the upcoming PS3 racing simulator Gran Turismo 6. Cars are unlocked with in-game credits, which can be earned through racing or paid for with real money. A million credits buys a few good cars. You can earn it in-game, or you can buy it instantly $10 in real world money. Small purchases made within a game are known as microtransactions, and they have a bad reputation.

Gran Turismo 6 is one of the latest title to face the internet’s wrath at the revelation that it includes microtransactions. Apparently, not many people like microtransactions. There are lots of reasons for this common hatred, which I’ll get to in a minute, but are all microtransactions equally repulsive? Is the revelation that a game includes microtransactions reason enough to dismiss it? Are microtransactions the mark of a greedy game publisher?

The only way we can answer these questions is to understand that there are different kinds of microtransactions and they can be found in different gaming contexts. Rather than accepting or rejecting all microtransactions, we should attempt to evaluate each implementation on the basis of its type and context.

Types of microtransactions

I think there are three types of microtransactions in games.

- Pay to unlock content

- Pay to win

- Pay to play

Pay to unlock content

This is the classic DLC model. The base game is either a complete standalone game that can be supplemented with additional content, or it is a barebones game acting as a demo where additional content can be unlocked in whole or in parts with additional purchases.

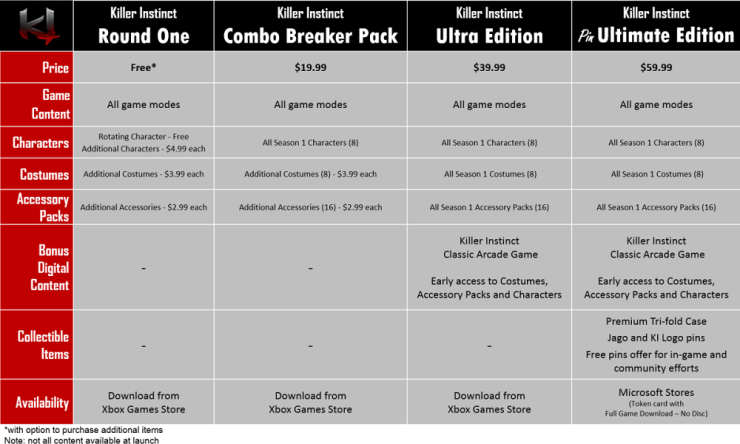

Examples are action RPG Mass Effect 3, where the base game is a complete standalone game that can be supplemented with additional missions purchased for smaller amounts; and fighting game Killer Instinct on Xbox One, where the base game includes only one character and the roster can be expanded by purchasing additional characters in expansion packs.

This type of microtransaction is probably the most accepted. People have been getting used to paying for DLC throughout the last generation of games consoles. Paying to unlock additional content is generally quite transparent and ought not to stop players from enjoying the content available to them without additional purchases.

Where this can go sour is when additional content is required to fully enjoy or understand a game’s story. The aforementioned Mass Effect 3 relied heavily on the DLC missions “From Ashes” and “Leviathan” to give it a coherent story and to answer some of the player’s biggest questions.

Pay to win

This is paying to improve your in-game performance or to gain an advantage over other players. This might involve paying for superior weapons, armour or special abilities not available in the base game. Often, an in-game currency required to unlock items or speed up processes is paid for with real world money.

Examples are sci-fi action game Dead Space 3, where the player can craft better weapons using crafting resources, which can be collected slowly in-game or paid for with real world money; and cartoon village building game Smurfs’ Village, where progress in expanding your village depends heavily on the in-game currency “smurfberries”, which again can be paid for with real world money.

This type of microtransaction is very unpopular with traditional players, who believe that success should depend on a player’s skill and not on a player’s real world financial resources.

Another popular criticism is implicit in the simple question, “what’s the point?” What’s the point of playing a game if you’re just going to pay to win? Where is the satisfaction in doing that?

A third criticism is that this type of microtransaction tempts people, especially children, to spend too much money in a game, perhaps without realising it. Everyone has heard various stories of angry parents who discovered their child racked up a gargantuan bill on smurfberries or some such in-game currency.

However, this type of microtransaction has been enormously successful in generating revenue in mobile and casual games. A 2012 study reported that 91% of mobile game revenue comes from microtransactions, mostly of this type.

Pay to play

This is paying to unlock timed access to play a game. This might be as explicit as inserting a coin into a timed arcade machine or paying for an MMO subscription, or it might be as subtle as paying to eliminate an in-game cooldown timer that prevents a player from continuing until the cooldown has expired.

Examples are fantasy MMO World of Warcraft, where players pay a regular monthly subscription for access to the game; and mobile racing game Real Racing 3, where a player’s car must be “repaired” after a race and cannot be driven again until it has been repaired (requiring several hours of real time) – a process that can be skipped by paying real world money.

The subscription model is generally well accepted among players, although its success seems to be limited to a handful of games that retain a faithful contingent of players, such as World of Warcraft and Eve Online. Many other games that were unable to generate enough revenue through subscriptions, such as Star Wars: The Old Republic, have removed the subscription charge and instead charged for in-game content (pay to unlock), in-game items (pay to win), or to eliminate cooldown timers (another form of pay to play).

The model that requires players to pay to eliminate cooldown timers has not been well received. Real Racing 3 received a very mixed critical response, with IGN praising its microtransactions and Trusted Reviews lambasting them.

Contexts of microtransactions

Microtransactions can crop up in different types of games, with different consequences. The contexts to consider are:

- Full price game or free game

- Single player or multiplayer game

Full price game or free game

People expect a full price game to offer a complete experience. Most types of microtransaction in a full price game are frowned upon.

If you paid £40 for a base game that they demanded that you pay extra for the indisputably best weapon or – worse – that you pay regularly to eliminate a cooldown timer that is preventing you from playing your game, then you would have good reason to feel ripped off.

The only really acceptable kind of microtransaction in a full price game is payment for additional missions or areas to explore, unless they are perceived to be essential to the game’s story, in which case you could reasonably ask why that content wasn’t available in the base game.

In “free” games (that is, games without an initial purchase price), the question of microtransactions is much more complex. Most people understand that a game’s developers and publishers must make money from their game, so few people expect a high quality game to be completely free. So which types of microtransaction are most acceptable in a nominally free game?

Pay to win often feels meaningless, while pay to play feels like a never-ending drain on your wallet. But maybe it only feels that way to people who are used to paying and playing in a traditional way.

For traditional players, it can be almost impossible to truly enjoy a game based on either of these models, because instead of getting immersed in the game world you are constantly aware of the next looming demand for real world money before you can progress. They are more comfortable paying a higher initial purchase price than being nickle-and-dimed through microtransactions.

For new or casual players, small microtransactions are probably easier to stomach than a high initial purchase price. After all, if you’re not really sure that you like spending time playing games, and you don’t habitually read news and reviews for the latest game releases, you might feel more comfortable paying a little to play a little than paying a lot for something you might not enjoy.

Single player or multiplayer game

In single player games, microtransactions are very difficult to justify. This is probably because players tend to be more rational when playing and investing in a single player game. Pay to win cheapens the experience, while pay to play feels like a waste of time. The most common type of microtransaction in single player games is pay-to-unlock-content, such as additional missions that can extend the life of a game and give a player more to see and do in a world that they love.

In multiplayer games, microtransactions are easier to justify on the basis that people are more willing to pay to be the best and to keep on playing to retain and advance their position. Both pay-to-win and pay-to-play models are common in multiplayer games. But they are not universally popular. Pay-to-win in competitive multiplayer has many vocal critics, who believe player skill and mastery of the game is all that should count.

The expendables

So there are lots of different types of microtransactions, and different contexts in which they can appear. There are all sorts of combinations, some good and some bad. But what’s the verdict on microtransactions?

We all want an easy answer, a straightforward way to look at a game and its business model and to be able to say either “this is good” or “this sucks, I’m not paying for that!” This is where you might expect me to say that there is no easy answer, but actually there is. In fact, there are two fairly easy answers.

I think there’s a clear distinction between two families of microtransactions (combinations of type and context), where one family is much easier to accept, for both traditional players and people with a sense of fiscal responsibility.

First easy answer: There are microtransactions that are permanent and microtransactions that are expendable. In general, paying for something permanent is better than paying for something expendable.

Microtransactions that add content permanently to your game experience, such as additional missions, lands to explore, or cars to drive, can be a worthwhile expenditure to improve a game that you already enjoy.

Microtransactions that add expendable resources, such as time or in-game currency, are typically part of a model that offers an endless grind. They simultaneously allow you to play a game and bend the rules of a game until it is barely a game, in the traditional sense, at all. They do not improve a game; at best they prolong it, and at worst they destroy it.

Second easy answer: Pay for what you think has value to you.

This might sound like a cop-out, but when people talk about the market deciding how much something is worth, that’s a matter of thousands of individual decisions taken by each of us.

Everyone needs to look at the potential microtransactions in a game they are interested in and decide for themselves: “will I pay for that?”

If microtransactions in any given game seem worthwhile to you, then go ahead, spend and enjoy yourself. If they don’t seem worthwhile to you, then move on and find a game with a business model you can get on with.

It’s really as simple as that. I think if you’re wise, you’ll look for permanence rather than expendables. But whoever you are, just make up your own mind. Together, all of us spending or withholding our money will move the market in the right way.

One Pingback