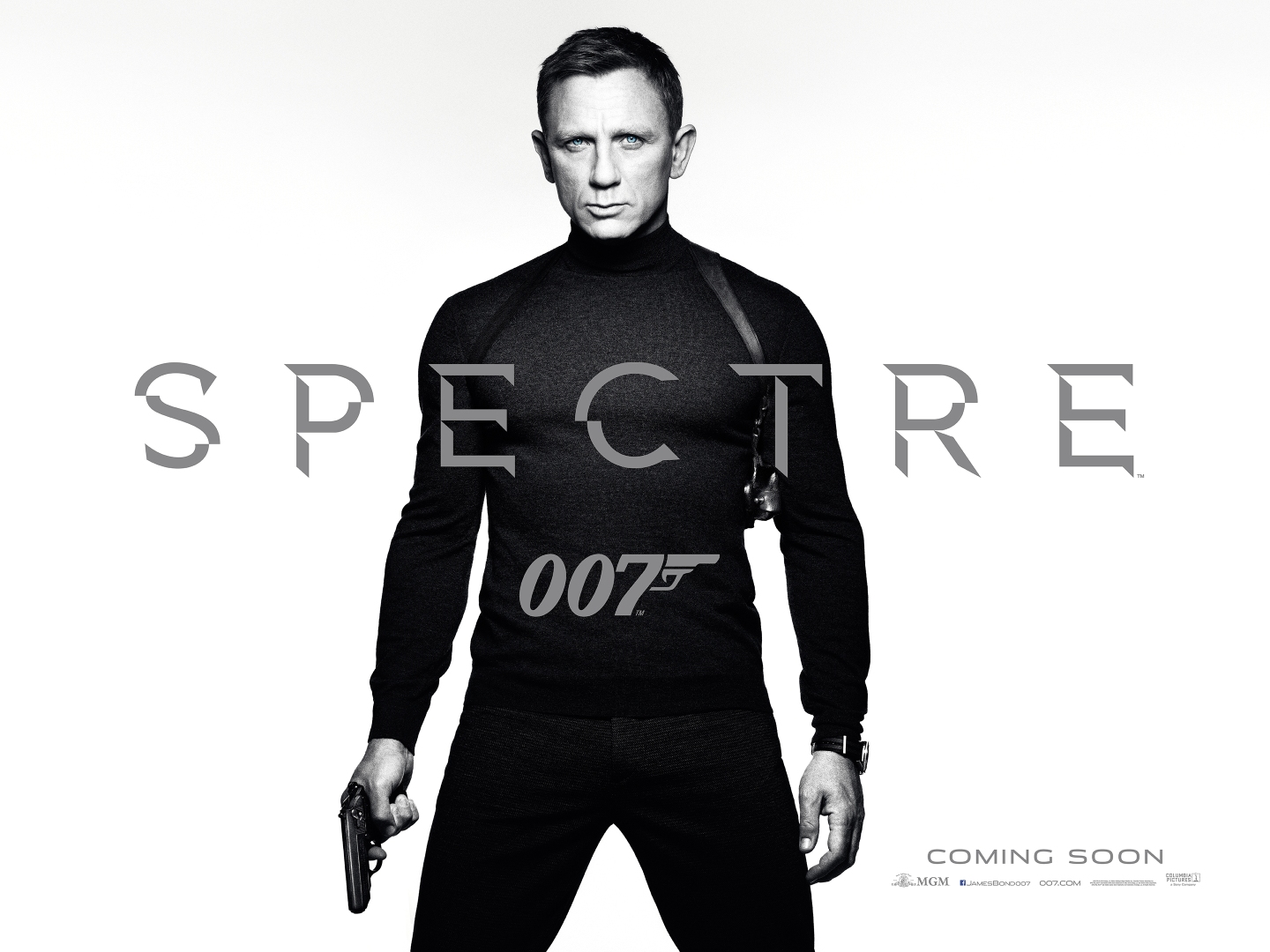

James Bond’s latest outing in Spectre successfully blends the best elements of previous Bond films. It’s not as unique or as focused as Casino Royale or Skyfall, but it is more entertaining and more recognisably Bond. Like 2002’s Die Another Day, Spectre wants to celebrate Bond’s long cinematic heritage; but unlike Die Another Day, Spectre knows which bits are worth keeping, which bits we can do without, and what needs to change to keep Bond moving forward.

Die Another Day was Pierce Brosnan’s farewell tour as James Bond. It also marked the 40th anniversary of Dr No, the first Bond film in the established canon. As such, it was the perfect vehicle to showcase the best of Bond and to give Brosnan the opportunity to go out on a high. Unfortunately, things didn’t go quite as planned and Die Another Day is now frequently cited as the worst Bond film of all time.

The version of “Bond film” on display here was a collection of all the most tired and tonally aberrant elements from Bond’s history, all blown to excess.

If nothing else, Die Another Day was instantly recognisable as a Bond film. A bikini-clad Halle Berry steps out of the water and catches Bond’s eye, following in the footsteps that Ursula Andress trod 40 years before. Bond faces a laser-based death trap, as he did in Goldfinger. He drives an Aston Martin packed with gadgets. And he surfs his way to safety, as he once did in A View To A Kill.

There were obvious problems in the execution in Die Another Day: most notably and embarrassingly, the scene where Bond surfs atop a tsunami features compositing effects of the worst order. But the larger problem was in what Die Another Day used for its inspiration. The version of “Bond film” on display here was a collection of all the most tired and tonally aberrant elements from Bond’s history, all blown to excess.

When he returned in 2006 in Casino Royale, it was as a leaner, stripped-back Bond without any of the paraphernalia with which the series had come to be associated.

“Bond girls” have always been a bit of a rubbish concept – one third eye candy, one third damsel-in-distress trope, one third plot device. The contrived death traps were impossible to take seriously after Austin Powers lampooned them (sharks with lasers on their heads, anyone?). Bond’s cars and gadgets frequently became deus ex machina devices, useful for solving sticky plot problems in the absence of any real ingenuity. And why on earth would you make a surfing scene that takes after the one in A View To A Kill, one of the worst scenes in one of the worst Bond films?

It’s no surprise that the Bond franchise disappeared from our screens and was mired in turmoil for four years after Die Another Day. When he returned in 2006 in Casino Royale, it was as a leaner, stripped-back Bond without any of the paraphernalia with which the series had come to be associated. Vesper Lynd was not a “Bond girl” in the traditional sense: she was a competent and intelligent woman, with actual agency and motivation beyond the influence of Bond himself. There were no evil lairs or contrived death traps; instead Bond is held in a nondescript building and tortured brutally. Bond gets to drive an Aston Martin, but crashes it within minutes. And where the opening chase through a construction yard could have taken a trendy turn by having Bond follow the parkour moves of his target, it instead portrays Bond as a decidedly untrendy bruiser, as he crashes through the scenery in pursuit of his nimbler, more sophisticated prey.

Bond is typically portrayed as a cypher, or an empty vessel for masculine fantasies: a man never shaped by his past or interested in the consequences of his actions in the present.

Casino Royale was barely a “Bond film” at all, but it was good. It told a story of modern terrorism and economics, underpinned by forces of greed, love, betrayal and brutish violence. It made Bond relevant in a way he hadn’t been in years.

Sam Mendes‘ first turn in the director’s chair resulted in 2012’s Skyfall, which in some ways continued Bond’s reinvention. Bond is typically portrayed as a cypher, or an empty vessel for masculine fantasies: a man never shaped by his past nor concerned with the future. But in Skyfall, we discover where Bond came from – his family and his childhood home – and we see his confidence in himself and his country both tested. Skyfall presented Bond for the first time as a vulnerable human being, and was all the better for it.

But Mendes also took the opportunity in Skyfall to begin to rebuild classic elements of the Bond franchise. Moneypenny is back, but as a field agent, not a secretary. Q returns, but as a young and quick-witted tech genius. There are visual nods to past Bond films: the komodo dragons recalling the shark pool from Thunderball; the Aston Martin DB5 straight from Goldfinger; and Raoul Silva’s toothless resemblance to the arch henchman Jaws. But the film never relies on these elements, using them – with a nod and a wink – only as the occasional decoration.

These classic Bond elements help make Spectre a grander and more easily entertaining film than the preceding films in the Daniel Craig era.

So Mendes was primed, with Spectre, to return Bond to his former glory. Spectre keeps the best of what came from Bond’s reinvention: the base violence and the nasty reality of Bond’s existence, which we saw in Casino Royale; and the hints of emotional realism from Skyfall. But it returns to the fold many of the elements that had been jettisoned along with the junk. Spectre sees the return of the powerful henchman, the car chase, and the villain’s secret lair, none of which outstay their welcome or become cornerstones for a film that might be shaky without them. Rather, these classic Bond elements help make Spectre a grander and more easily entertaining film than the preceding films in the Daniel Craig era.

That’s not to say Spectre is without problems. Vesper Lynd casts a long shadow that neither Monica Bellucci not Léa Seydoux can escape. Bellucci’s character is used and forgotten about all too quickly, while Seydeux’s Madeleine Swann transitions swiftly and in unlikely fashion from resisting Bond’s advances to pulling him into bed, and falls into the clutches of the damsel-in-distress trope before the film is done. Bond’s explosive watch (I thought they “didn’t go in for that sort of thing anymore”) and blind luck get him out of a tight spot far too easily. And the dialogue tends toward the functional more than the poetic – although there are one or two zingers in there.

Still, even while Spectre feels like the most familiar Bond film in years, Mendes has been wise in changing the formula in key ways, which Bond must continue to do to remain interesting and relevant. Central to Spectre is the rare theme of restraint. Much of the plot revolves around a plan to launch a global intelligence data-sharing system, giving member nations unprecedented surveillance powers. M (Bond’s boss) questions whether this is a good idea, given the inevitable compromise to privacy and democracy, and invites a comparison with the double-0 program with its infamous and legally dubious “licence to kill“. M defends his agents by appealing to their human nature, and their capacity for individual moral judgement, which a blanket surveillance program and data-driven algorithms will never have. M delivers an important line in this debate: “A licence to kill is also a licence not to kill”. This has quite spectacular payoff when, in a significant moment, Bond chooses not to kill someone, despite great temptation upon his character and the typical demand for a grizzly death that comes with a climactic action scene.

It’s a risky departure from Bond tradition, but as Bond’s history has shown, the films must constantly change and strive to push forwards or else die a slow death. And so this change was a necessary divergence from Bond’s past, to safeguard his future. As Sam Smith sings in Spectre’s title song:

For you I have to risk it all

Cause the writing’s on the wall

The quality of mercy on display in Spectre transforms Bond for the first time from a necessary evil into a genuine hero.

Bond has never been known for his mercy or restraint. He has never before, to my recollection, chosen not to kill a villain when given the opportunity – even if they were unarmed. Overcoming Bond’s killer instinct while putting him under intense pressure moves Bond’s character forward in a meaningful way. It builds on the work done in the three previous films, of confronting Bond with horrific personal loss. Spectre lays bare the consequences of his actions; but rather than having Bond double-down on his desire for revenge or his violent tendencies, and hazard pushing the audience beyond sympathy and into revulsion, Spectre stays Bond’s hand.

The quality of mercy on display in Spectre transforms Bond for the first time from a necessary evil into a genuine hero. This one act can’t undo the countless times he kills in this film alone, let alone the important losses incurred in previous films, but it is significant for the idea it represents: that having the power to do something doesn’t necessarily mean that you should.

Between Die Another Day and Casino Royale, the Bond franchise took this lesson to heart. And with the advent of Spectre, so has James Bond himself.

A review to contemplate, after one has seen the film, I suggest, for all Bond Film aficionados. My favourites, opened by Tiger Bay’s finest: Goldfinger and Diamonds are Forever 00🔫

LikeLike